Is it not strange, some will say, to defend monasticism, which has existed already more than fifteen hundred years, firmly established by the testimonies and examples from the lives of numerous ascetics, justified in the profound writings of such theologians as Saint Basil the Great, Saint Gregory the Theologian or Saint Theodore the Studite, its roots embedded in the bosom of Christianity and its history, become the stronghold and the adornment of the Church?

Monasticism, in fact, can find for itself an entire cloud of witnesses and advocates. Nevertheless, it is even to this day subjected to constant attacks by its many opponents who seek to deny it of its very right to exist.

If they have been scandalized only by the examples of those among monastics who lead imperfect lives and who defile and demean this lofty calling, then their negative attitude towards monasteries and monasticism in general would have some basis. But to judge monasticism as a whole is not appropriate.

But the world, that is, human society formulates its life not according to the Commandments of Christ, but according to the spirit of this age and thus does not comprehend even the ideal of monasticism, considering it wrong and foolish, thus proving, more than all else, that monasticism in its essence is a phenomenon that is not of this world. The words of Christ which He directed to His disciples apply fully to those in the monastic life: "If ye were of the world, the world would love his own: but because you are not of the world, but I have chosen you out of the world, therefore the world hateth you" (St. John 15:19).

A monk, as is proven by the word itself (Greek: monos, one, alone), is always and everywhere alone. He is separate from the elements of the world, even though he might live in the midst of a noisy city. The majority of humanity sees in him something of an alien quality which is unfamiliar to them.

It is surprising that even those who are of the faith and evidently close to the Church often show a lack an understanding of the monastic ideal, which for them remains inconsistent with their usual notions. They are ready to grasp and accept every act of service to the church--pastoral, missionary, philanthropic, educational, and all other paths of Christian life--except that of monastic asceticism. In the course of centuries the latter has manifestly become a disputed standard around which the struggle over application does not subside, while the principle theoretical polemics have grown ever stronger during this period of the moral decline of Christian life.

Spiritual qualities, according to the words of the Apostle, are discerned by the spiritual. "But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God...because they are spiritually discerned" (I Cor. 2:14).

Life constantly demands of us the ascetic struggle of self-restraint, and even at times self-renunciation, and we are subject to its command, willingly or not, then the monastic accomplishes nothing contrary to the nature of things and still less contrary to the moral law by adhering to the path of inner and outer asceticism: he only goes deeper and further than others in that direction, in harmony with the goals he has set himself--the purification of the soul and body in order to prepare himself for another, eternal blessed life.

It is for the attainment of this aim that the monastic withdraws, first of all, from the world--not from the world as the beautiful creation of God, but from the world which lies in evil, rampant with seductions and temptations. Of course, he cannot withdraw from himself, from his own sinful nature, but, by withdrawing from the external, worldly impressions which distract the mind and feed the passionate urges of the soul and body, he enters more deeply into his inner cell in order to keep watch over himself, as the ascetics put it, and gradually attains complete victory over the passions and the world of the soul.

Our soul is like the most sensitive photographic plate: it involuntarily imprints on itself all that it sees or hears around it. Therefore, surrounding society exerts a greater effect upon us than we ourselves notice. The ewll-known saying of the Psalms: "With the holy man wilt thou be holy…and with the elect man wilt thou be elect, and with the perverse wilt thou be perverse" (Psalm 17:26-27), is daily vindicated in life. Man is made such that he ever strives to assimilate the views and attitudes which dominate around him in the order of social life. Even the most forceful personalities are not able to resist the depersonalized influence, the so-called public opinion and way of life, which despotically demands subjection to itself from each person.

The more the monastic secludes himself from the world, the farther he will flee from temptation. This is why the dispassionate wilderness becomes for him a lovely place. There he, as it were, finds himself. Not idly did one wise man say: "The more I am with people, the less human I feel myself to be." With its untroubled peace and serenity "the wilderness listens to God" and therefore becomes the best converser and tutor for monastics.

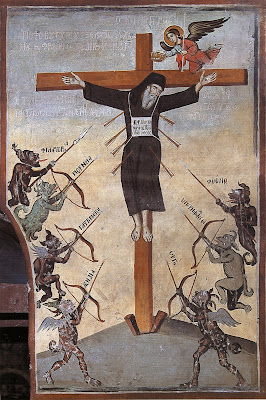

The monk must purify himself of all the passions, beginning with the crudest and ending with the most subtle and scarcely perceptible. He must humble himself and enslave his flesh which rebels against the spirit, crucify his self-love and pride, which engenders a dangerous "isolation.: IN a word, he must follow unswervingly the path of ascetic struggle so that in going from stage to stage he can finally attain perfect love of God, and with is also love for his neighbor, realizing the acme of Christian virtue and the crown of his spiritual activity.

With sincere agape in His Holy Diakonia,

The sinner and unworthy servant of God

+Father George

Written by Metropolitan Anastassy

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.